WARNING: The following contains major spoilers for The Other History of the DC Universe #3 by John Ridley, Giuseppe Camuncoli, Andrea Cucchi, José Villarrubia, and Steve Wands, on sale now.

The Other History of the DC Universe focuses on reexamining the events of the DC Universe from the perspectives of several of the publisher's prominent marginalized characters. The first two issues focused on the perspective of three of DC's prominent African American heroes, Black Lightning, Bumblebee, and Mal Duncan. The third issue, though, chooses to examine the East Asian perspective in the DC Universe through the lens of Katana.

Katana, aka Tatsu Yamashiro, first appeared in 1983's The Brave and the Bold #200 by Mike W. Barr and Jim Aparo. Tatsu is best known as a member of the Outsiders, a team formed by Batman in the 80s. Throughout her history, she has also been linked to several other teams, including the Suicide Squad, the Birds of Prey, and even the Justice League.

The issue's primary focus is not on her heroics, but instead on her humanity and her experience as a Japanese woman in America. Much of the issue recounts Tatsu's feelings of alienation from mainstream society. She recounts how this is to be expected in a country with such a complicated and sometimes hostile relationship with East Asian immigrants and Asian Americans. The issue itself even points to how some of this racism was baked right into her origins, and even seeks to correct that.

Tatsu's transformation into Katana has always portrayed her as coming from humble origins. As opposed to having come from a long line of samurai warriors, Tatsu was nothing more than an average Japanese woman. She eventually found herself caught in a love triangle when two brothers, Maseo and Takeo, both proclaimed their love for her. Tatsu, however, chose Maseo as her husband, a fact Takeo did not take well. Takeo eventually joined the Yakuza and was disowned by his brother. Meanwhile, Tatsu and Maseo started their own family and Tatsu gave birth to twins, Yuki and Reiko.

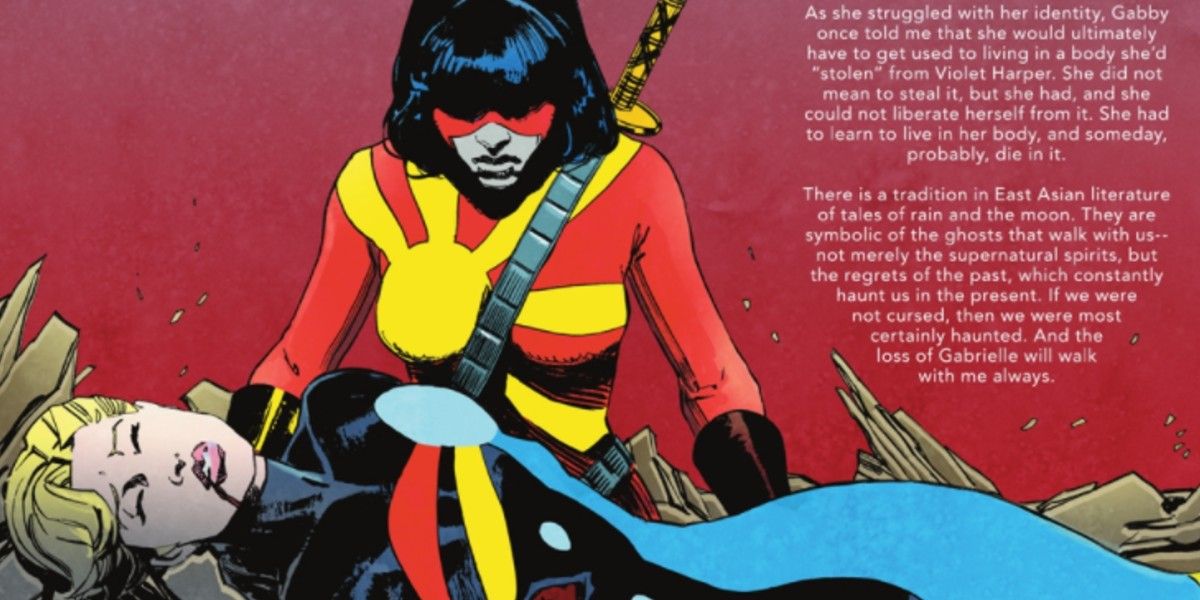

However, Takeo would eventually return into their lives, still spurned by Tatsu rejection and armed with a sword forged by the fabled swordsmith Muramasa called the Soultaker. Takeo used the Soultaker to kill his own brother and Tatsu's husband, Maseo, and then set fire to their house killing both Yuki and Reiko. All of this was witnessed by Tatsu, who engaged Takeo and disarmed him, even though Takeo himself got away.

In the original telling of Katana's origin, she attempts to save her children from the fire, only to hear a voice coming from the sword telling her that they are already gone. Taking what she hears as truth, she then escapes her burning home. The voice, as it would turn out, was Maseo's, his soul having been trapped in the sword upon being killed with it. The sword apparently had the ability to absorb the souls of all those it killed, hence the name Soultaker.

This mystical element would become one of the primary traits of Katana's character for many years. She eventually undertook samurai training under the tutelage of a master named Tadashi. She became a master assassin and gained a reputation for two things: her master swordsmanship and her propensity to "speak" to her dead husband trapped in her mystical sword.

Maseo would eventually move on to the afterlife and his soul would be replaced with Takeo's after Katana tracked him down and killed him. But, the mystical properties of the Soultaker became a cornerstone of Katana's character. It is this element, however, that Ridley retcons in this issue.

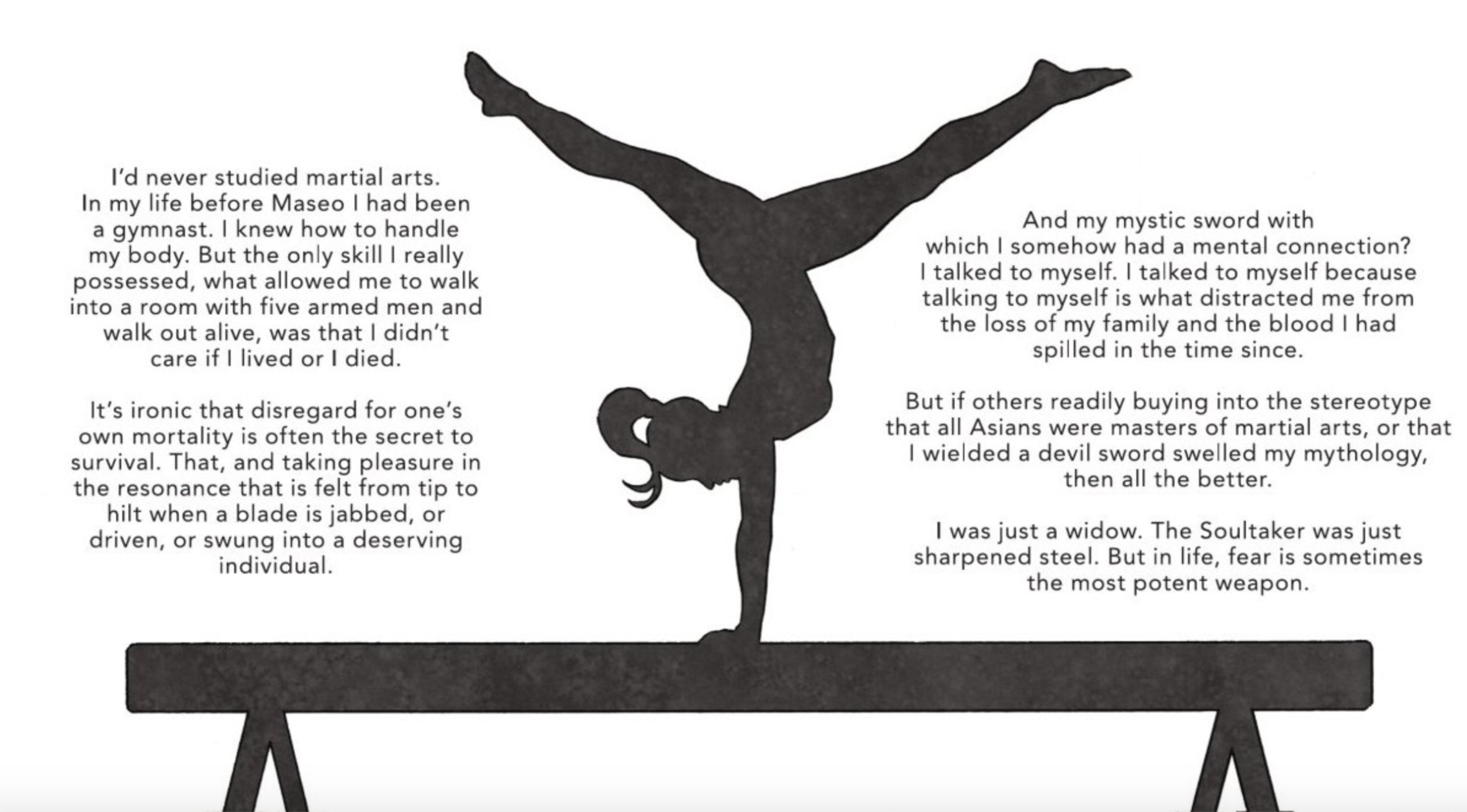

In Ridley's reimagining of Katana's origin, the Soultaker never actually possessed mystical abilities. All of the talking she did to the sword was really her processing her grief. Katana, for all intents and purposes, was just a "normal" assassin with no link whatsoever to the supernatural. She only allowed the rumor to persist because it added to her feared persona.

With this retcon, Ridley calls out a persistent issue in the representation of Asian characters in media and subverts it. Specifically, he refers to the stereotype of an inherent link between Asians and the mystical or the "Magical Asian" trope. This trope refers to the typical depiction of Asian characters as martial artists, practitioners of traditional medicine, or sages of ancient religion. The role of these characters is usually to dispense wisdom or guidance, usually to white protagonists.

Katana may be a character that is her own protagonist and a woman of her own agency, but ultimately the mystification of her origin lends itself to this trope. She is also far from the only example. This same stereotype pops up in countless films, television shows, books, and video games.

The exoticism associated with Asian culture in Western media served a purpose: it perpetuated the otherization of Asian people. It's no coincidence that these tropes first began appearing in American film and pop culture at a time when the U.S. government was becoming increasingly hostile toward Chinese and Japanese immigration into the country. The propagation of these portrayals accompanied increased xenophobia against Asian immigrants among native-born Americans and the passage of racist laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Whether Ridley's overwriting of this part of Katana's past will translate into her depiction in the mainstream DC Universe is yet to be seen. However, it does at least spark a conversation that needs to be had.

Calling out these stereotypes is not meant as a condemnation of these characters' existence. As with all things, their depiction has changed and evolved with time. Indeed, some of these characters have gone on to become fleshed out and well-developed, serving important roles in their respective universes. What Ridley is doing here is simply calling attention to a persistent trope that pops up more times than we care to admit. And sometimes, that's the first and most important step.

0 Comments