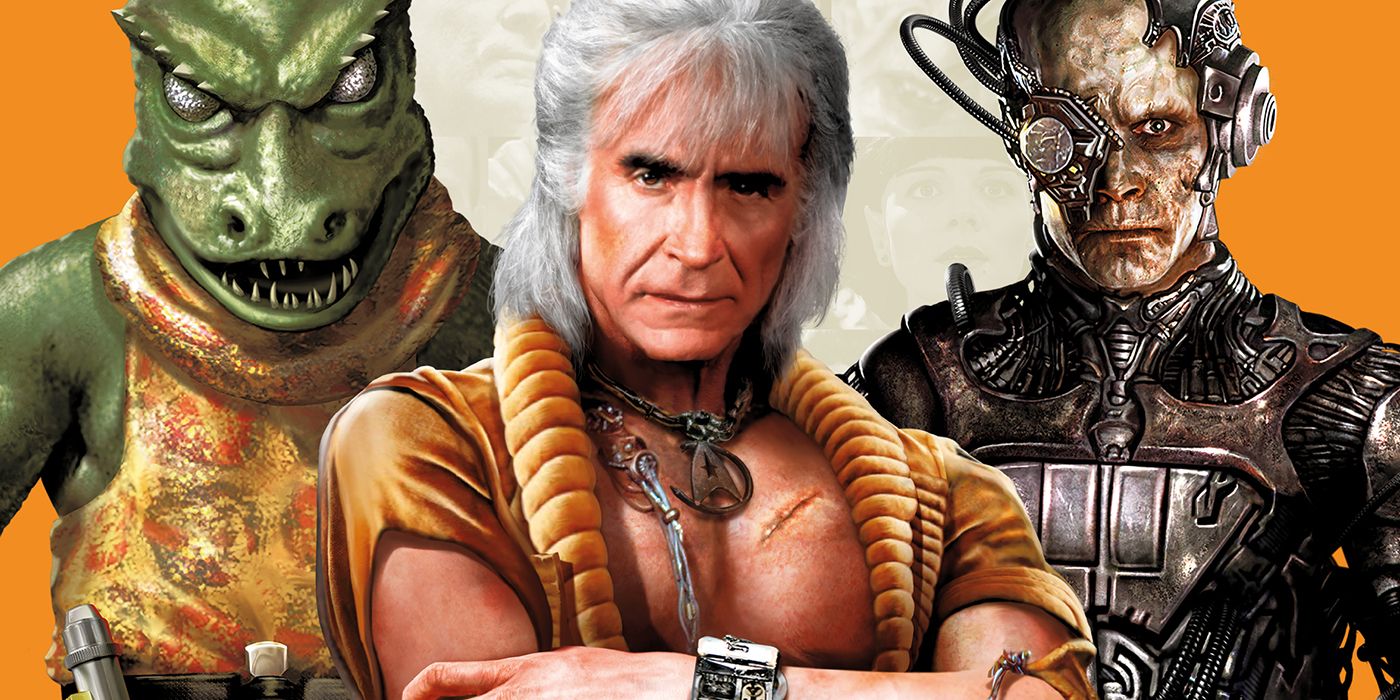

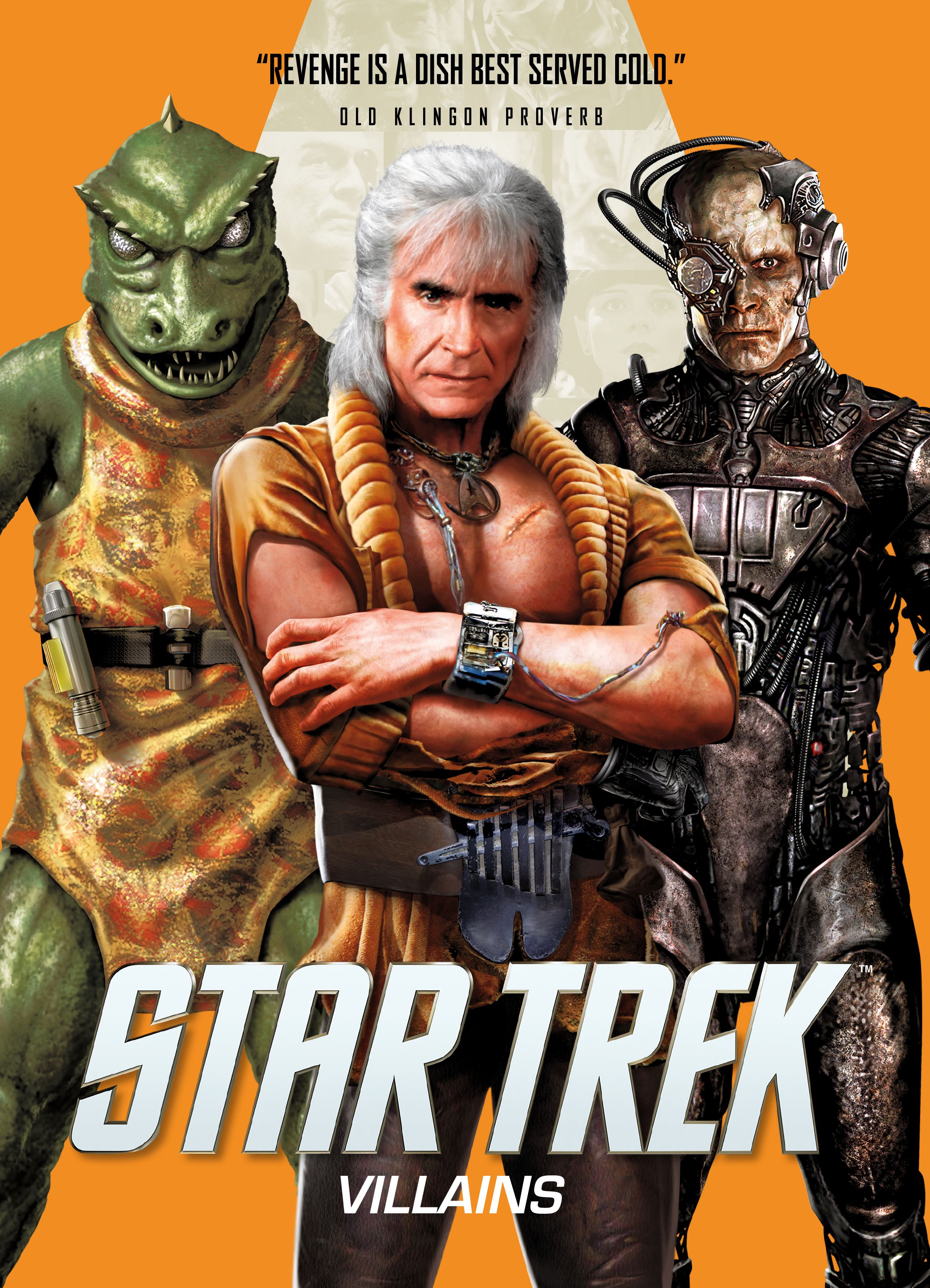

Of all the sci-fi franchises, Star Trek boasts possibly the most compelling villains of them all. A new essential guide looks to put the focus on these antagonists through a wide range of interviews and character spotlights.

CBR has an exclusive excerpt from Star Trek: Villains, an upcoming release from Titan Comics. The excerpt is called "The History of Shinzon" with words from author Christopher L. Bennett. Portrayed by Tom Hardy, Shinzon has a unique relationship with Captain Picard, and as the excerpt reveals, there are many layers to the Star Trek villain.

Is it nature or nurture that creates a villain? One of the conflicts at the heart of the final Star Trek: The Next Generation movie, Star Trek Nemesis, saw Captain Picard face a clone of himself – but one raised in the Romulan Empire…

What makes a good Star Trek villain? Is it just someone dangerous and larger-than-life, or should there be more? Star Trek at its best is a character-driven drama that examines and celebrates the human potential. So what could be better than a villain who has a strong, rich emotional relationship with the hero and who serves as a vehicle for examining human nature?

Of all the movies’ antagonists, Shinzon of Star Trek Nemesis has the most complex, personal relationship, as well as the most face-to-face interaction, with the captain of the Enterprise. A clone created for an abandoned Romulan plan to replace Picard as a deep-cover spy, Shinzon grew up an abused slave in the mines of Remus, bonding with his Reman protectors. Possessing Picard’s innate intelligence, drive, and leadership, Shinzon rose above this. Sent into the Dominion War as cannon fodder, he emerged with an unbroken string of victories, winning the respect of the Romulan military and their backing in his eventual coup.

But despite his achievement, the clone remains fixated on his original, luring Picard to Romulus on the pretext of peace. From the start, Shinzon focuses on his shared identity with Picard, telling the captain, “I feel exactly what you feel.” He argues that he and Picard are essentially the same man, differing only by upbringing: “If you had lived my life... you would be standing where I am.” The story of Nemesis is driven by the evolving relationship of these two facets of the same man. Their interplay raises fundamental questions of identity and destiny. Are good and evil innate, or can the same man take either path depending on his circumstances? Is our nature determined by birth? By upbringing? Or do we have the power to choose who we become?

Though the two men initially bond over their shared thoughts and aspirations, Picard soon learns of Shinzon’s plans for conquest. In the face of the captain’s disappointment, the clone again insists that Picard would do exactly the same “had you lived my life.” He argues that his actions are justified by his traumatic past, and he resents Picard for his happier life. Picard counters that “I’m a mirror for you as well,” that Shinzon has the ability to put their shared nature above his nurture and make himself a better man.

But Picard has the advantage of maturity. He realizes that Shinzon is much like himself at the same age: “selfish, ambitious, very much in need of seasoning.” The clone has Picard’s innate gifts but none of his hard-earned wisdom and discipline. He blames his behavior on his circumstances, on the Romulans who abused him. As long as he denies his own culpability for his actions, he can never learn or grow, and this is the key difference between the two. Picard does not blame his fate and failings on others, so he recognizes that the power to change lies within himself.

However Picard’s effort to convey this message falls on deaf ears, for of all the people Shinzon blames for his troubles, Picard tops the list. “My life is meaningless as long as you’re still alive,” he tells the captain. There is literal truth to this; without a transfusion of Picard’s genetic material, the clone is doomed to die young. But more fundamentally, he resents Picard as the original of whom he is a mere copy. He cannot truly embrace his adopted identity as Shinzon of Remus as long as he is merely an echo of a human voice. His assault on Earth is the final act he must perform to gain total freedom. Before Shinzon can truly emerge as his own man, he must eradicate both Picard and his achievements, his legacy. Picard has earned greatness by saving Earth and the Federation; so Shinzon must outdo him by destroying them. “And my voice shall echo through time long after yours has faded to a dim memory.” Ultimately, though, Shinzon is unable to escape his ties to Picard. Even when he gains the edge in battle, his need to look Picard in the eye and gloat leaves him vulnerable to a crippling counterattack. Finally, he destroys himself trying to ensure that Picard dies with Shinzon’s hands at his throat. To the end, their conflict is intensely personal.

Essentially, Shinzon is a son rebelling against his father, resenting his overshadowing influence even while craving his recognition. Picard, in turn, tries to fill the paternal role and offer guidance to the prodigal child, but must face the tragic reality that it is too little and too late. It’s that emotional subtext between Patrick Stewart and Tom Hardy, along with the philosophical questions, that anchors the fanciful story in something meaningful and human. To me, at least, the relationship between Picard and Shinzon is the richest, most dramatic, most thought-provoking hero-villain dynamic in any Star Trek film, and it makes Nemesis one of my favorites despite its acknowledged flaws.

“It was really, really good fun to play the villain. You have so much freedom when you play villains. There are so many avenues you can explore.

“A baby is not born evil, I don’t believe personally. I think that you attain baggage through circumstances, through various issues with the world. Shinzon is very much the orphan, the lonely child who was abused. Unless you get right to the centre or the essence of a character, there’s no point.

“Also, when it comes to villains, why is this person a monster? Why is someone suddenly so vile and distasteful? Because of what he’s been through. That makes for understanding a character. Three-dimensional bad guys are much more interesting than one-dimensional bad guys.” [interviewed in 2003]

Star Trek: Villains goes on sale Sept. 21, and is available for pre-order.

Source: Titan Comics

0 Comments