Welcome to the 15th installment of Page One Rewrite, a look at lost comics-to-screen adaptations. Over 30 years have passed since Tim Burton's Batman, which altered the Dark Knight's image and became a pop-culture phenomenon. Much of Batman's early development has been documented, with screenwriter Sam Hamm, now writing a comics continuation of the movie, offering insights into the story's evolution. An earlier attempt by producers Benjamin Melniker and Michael E. Uslan to make Batman in the 1980s, possibly starring Bill Murray, has also been detailed.

What's less known is the period between Mankiewicz's draft and Hamm's screenplay. Most aren't aware that Burton himself co-wrote a detailed treatment with his then-girlfriend, Julie Hickson, shortly after he was hired to direct. Dated Oct. 21, 1985, the 45-page document is labeled an outline, but given its level of detail, it would qualify today as a "scriptment."

The opening lines describe Gotham as "a little New York, a little Max Fleischer, a lot Fritz Lang's Metropolis." The Fleischer influence evokes Burton's past as an animator, and the Metropolis inspiration foreshadows what could be the 1989 film's most impressive achievement, and Burton's greatest influence over the mythos.

His Gotham City isn't bound by a calendar or any strict logical thinking. It can be the mid-1980s, but Gotham could look as if it's a city lost in time. Men can wear fedoras, art deco skyscrapers can reach into the heavens, gargoyles can guard churches, and a derelict with nasty habits could be lurking in the alleys wearing stained jeans and Nikes. In Gotham, all can coexist.

The visual description goes on to detail sci-fi inspired aerial tramways, brightly colored blimps, and even more Fritz Lang architecture. The grittiness of the 1989 film isn't quite here yet; we soon discover this opening scene is set 20 years earlier. The old Gotham is described as more "gaudy" than anything, but it's clear the city is a character in itself, and not a setting you can fake by shooting exteriors in Pittsburgh.

In the midst of a summer heatwave, a mid-30s Thomas Wayne is delivering a speech at city hall, warning of mob infiltration into Gotham's unions. He publicly accuses a "lumpish, brooding" Rupert Thorne of mob connections. Watching above in the balconies is a 10-year-old Bruce Wayne.

Thomas Wayne makes it all the way to Wayne Manor without any unpleasant encounters in Crime Alley. Bruce and Thomas horseplay, to the bemusement of the dry, proper Alfred Pennyworth. Here, he's the "beloved family butler," a role Frank Miller has yet to retcon him into with 1987's Batman: Year One.

Thomas confides in Alfred that he fears exposing Thorne will place his family at risk, and asks Alfred to care for Martha and Bruce if anything happens to him. It's another bit that predicts Alfred's expanded role in the mythos: Both the Batman: Earth One graphic novels and the TV drama Gotham have a toughened-up Alfred acting as young Bruce's defender.

Martha Wayne enters, dressed in a "breathtaking fairy costume," as Bruce reappears, now dressed in a harlequin outfit. The family enjoys dinner, then goads Thomas into trying on his own regalia. He reemerges, dressed in a "majestic bat costume which itself looks like the showpiece of some magnificent opera."

Given that Burton is open about his ignorance of the source material (mainly reading contemporary work by Miller and Alan Moore as research), it's curious to see Thomas dressed as a proto-Batman. That would seem to be a nod to the infamously goofy story "The First Batman," from Detective Comics #235, which established that Thomas wore a "bat-man" costume to a party shortly before his murder. Today, of course, the Flashpoint alternate-reality Thomas Wayne who operates as his own ruthless Batman has earned a fan following. Perhaps Julie Hickson was picking up Burton's slack in the lore department.

Alfred takes a super-8 home movie of the family before they head out to the performance of Der Fledermaus, an operetta by Johann Straus that's doubling here as a masquerade ball. Two mystery figures shadow the Waynes during the party. At midnight, Thomas decides it's a beautiful night and suggests they walk home. Doing so in costume, during "the witching hour," causes him to smile. Martha, reluctant, allows Bruce to be the deciding vote.

It's admirable that there's an effort to give Thomas some personality before the inevitable, as well as establishing young Bruce's happy home life. There's no traumatic fall down into a cave, no stern lessons about the harshness of life. Before the tragedy, Bruce is a blissful kid with no worries. But what he'll never forget is his role in sending his family into that alley.

The first truly questionable deviation from the lore comes next, when the Waynes are killed by… a drive-by shooting, courtesy of a Mr. Softee ice cream truck. To be fair, the script is a year away from Miller's iconic origin flashback in The Dark Knight Returns (the version that popularized Martha's falling pearls), which likely inspired the version eventually seen in 1989's Batman. Young Bruce eyes his parents' murderer -- around 17, with chalk-white skin and red lips -- as the truck drives away.

The first act ends with a voiceover from adult Bruce, revealing on that day, his war on crime began. Act Two opens with a training montage, with a Burton twist: This Batman also studies advanced hypnosis, magic and witchcraft. He grows close to Commissioner Gordon, a family friend and mentor who admonishes Bruce to let go of his preoccupation with Rupert Thorne.

Alfred is Bruce's other confidant, aiding him in the construction of what becomes the Batcave. Bruce obsessively watches the home movie footage of his family, becoming fixated with the image of his father in a bat costume.

Years pass, and the Joker is an escaped felon, declaring vengeance against Gotham and its current mayor, Rupert Thorne. Under Thorne, Gotham has descended into chaos, becoming the grimier city we recognize from other 1980s interpretations.

Joker goes on absurdist crime sprees, and preempts television shows with his own demented broadcasts. (He somehow makes a cameo appearance on The Love Boat, joined by Cloris Leachman and Andy Warhol!) The Joker's antics inspire Bruce to don his new Batman costume. He prowls the city at Christmas time, already far more flexible than his eventual film version, scaling buildings with ease. The Joker has launched Gotham Square's Christmas tree into orbit, declaring the war he's launched on Christmas. Batman confronts the Joker for the first time, engaging in an elaborate fight sequence that moves from an outdoor ice skating rink to Gotham's rooftops.

Batman evades death when Joker throws him off a building (again exhibiting acrobatic skills we never saw in Burton's films, thanks to the stiff rubber costume.) As the public absorbs news of Batman's debut, Joker's manic crime spree escalates. By night, Batman learns the ropes of crime-fighting, while by day, Bruce Wayne charms Gotham's elite. One event is scheduled for the opera house where he spent his last night with his parents.

The opera is Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream, featuring Silver St. Cloud as its star singer, portraying Titania, the Fairy Queen (evoking memories of Bruce's mother). The Joker crashes the opera with another deadly prank. Bruce rescues Silver, and they have a romantic encounter that night, ending "years of psychic and physical abstinence."

Bruce sneaks away from Silver's sleeping body, returning home. (He'll later be treating Vicki Vale in a similarly callous way in 1989's Batman.) Here, the story introduces the Batcave and Batmobile. The Joker now has "Grimacing Gas," Bruce learns from Alfred, and has killed a comedy club audience with "violent paroxysms of laughter." Commissioner Gordon reacts by calling Bruce Wayne, asking for his aid contacting Batman, who he's reluctantly turning to for help. The Bat-Signal is soon constructed.

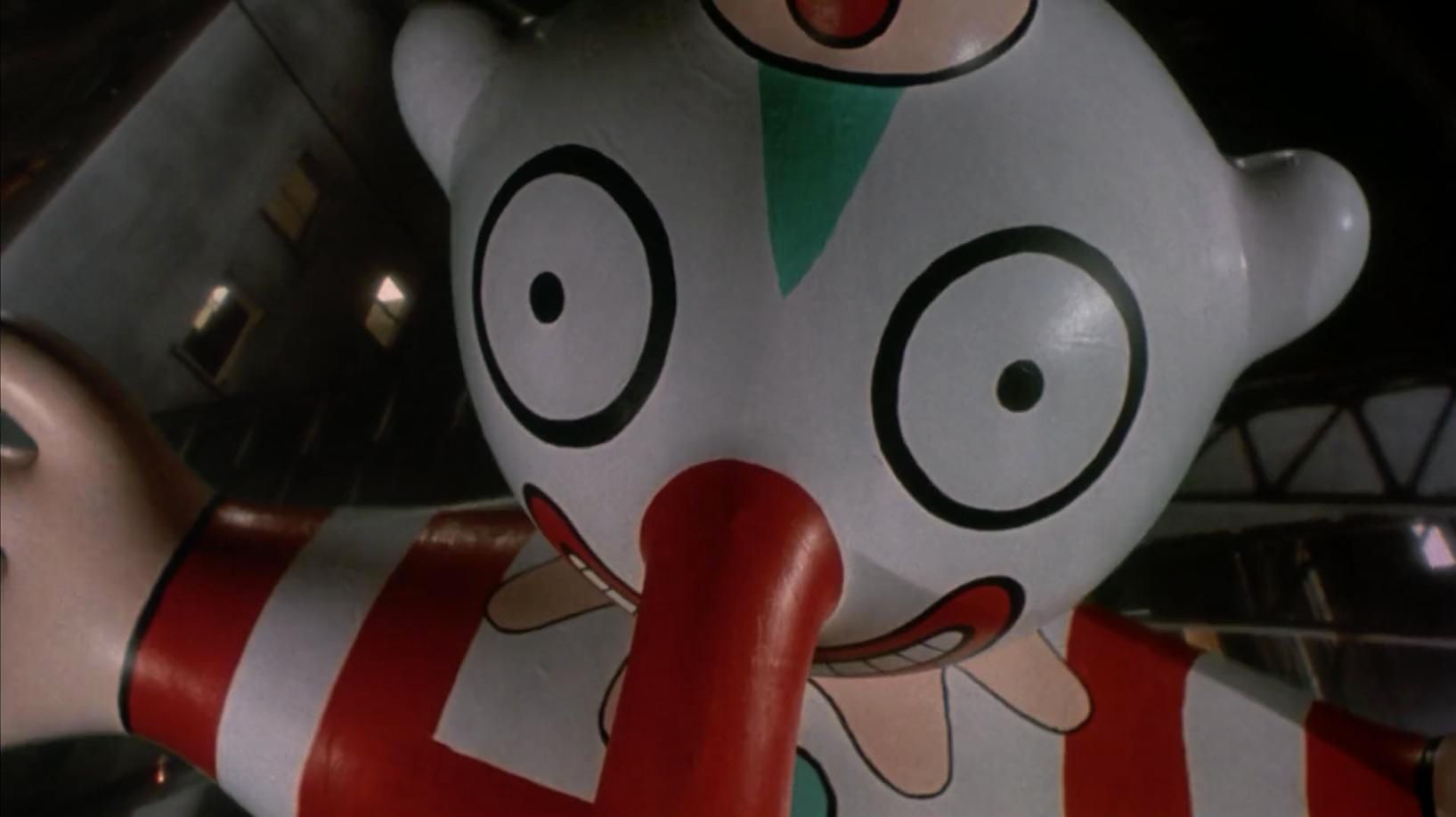

Later, Silver is Bruce's date at a charity circus performance, which is another public event crashed by the Joker. Surprisingly, this scene introduces Penguin, posing as the ringmaster, Riddler dressed as a clown, and Catwoman acting as a trapeze artist. Yes, three of Batman's most prominent foes are Joker flunkies — and they disappear after this scene. The Flying Graysons are there, meeting their predictable fate. Another questionable move makes Catwoman directly responsible for their deaths, after applying acid to their ropes.

The villains escape, as Bruce comforts a 10-year-old Dick Grayson. Weeks pass, and Bruce is in the process of adopting Dick, "a clever little wise-ass with a loving heart." Oddly, he's described as having carrot-colored hair, which was perhaps a reference to Jason Todd (still new in the comics as Dick's replacement, and initially dying his red hair black when in costume as Robin). They bond as father and son, with Dick demanding he join Batman on his missions.

More absurdity with the Joker has him dressed as the Mad Hatter and being interviewed by Barbara Walters, who's tied up and held at gunpoint. The Joker announces he's running for mayor against Thorne, promising his rampages will stop after his election. During a debate he soon conducts with a kidnapped Thorne, Joker shoots his opponent repeatedly in the chest. Somehow, through all of this, the Joker is gaining dedicated followers.

Nearing the film's climax, Bruce Wayne boldly announces his candidacy for mayor. Joker declares the election will be held on Christmas, and has a Christmas Eve parade in his honor. Bruce deduces the giant parade balloons are filled with poisonous gas — the Joker's followers have masks, and the rest of Gotham will die. He's sure to win the election now.

Evoking his father, Bruce makes an impassioned speech over Gotham's airwaves, calling on the public to reject the Joker, before sneaking away to change into Batman. He confronts Joker at his parade (with dialogue like "Hey, chalk-face! Feel like picking on somebody your own size?") Their fight has them hitching a ride on a runaway balloon, before Batman crashes dramatically through a museum's skylight, only seconds before Joker smashes through another window, riding his balloon.

Joker gains the upper hand, but Dick Grayson suddenly appears in his traditional Robin costume. The tide turns, and Batman has the Joker's gun pressed against his forehead. Batman demands the Joker reveal who paid him to kill the Waynes. Joker boasts it was Rupert Thorne… the man he's already killed, preventing Batman from gaining his precious vengeance.

Batman struggles with his temptation to kill the Joker when, suddenly, the gentle hand of Commissioner Gordon appears on his shoulder. The "spell is broken" and Batman allows Joker to be arrested. He runs off into the night with Robin, now free from demons and heading home for Christmas. There, Alfred and Silver join them for an idyllic Christmas morning… until Silver spots one last present under the tree.

It's a jack-in-the box, wrapped in purple-and-green paper. The film fades out with the sound of the Joker's laughter.

Joker conducts bizarre experiments in his Fellini-esque lab, including another nod to the comics, the eerily grinning Joker Fish. This seems to confirm writer Steve Englehart's claims that his comics were given to the producers as reference early in the movie's development.

Establishing the Joker has been The Joker since he was at least a teen feels very wrong. This was probably an attempt to address Joker being so much older than Batman in the earlier Mankiewicz draft. The eventual film still has a Joker as a young man, but not yet the Joker, when killing the Waynes.

Eventual Batman screenwriter Sam Hamm has stated Burton could never let go of the idea of Joker killing Batman's parents, as evidenced here. We also see Burton was thinking of a Christmas setting years before Batman Returns. Some of Joker's gags made it into the actual film, as did Batman's theatrical entrance through a museum's skylight.

Some of this doesn’t work, obviously. The structure of the film is odd, for one thing, as it seems nearly half of the runtime would've been devoted to various montages. Hamm's script turned this concept on its head, nixing almost all of Batman's origin material and replacing it with Joker's origin instead. By 1989, the decision had also been made to nix Robin, which was probably the right call.

However, this draft is telling a different story thematically than the '89 film, and Robin's presence is more than nostalgia bait. The '89 movie is a rather straightforward revenge story that ends with the villain dying, possibly because the hero allowed it. Batman doesn't evolve much as a person; in fact, the final moment between Alfred and Vicki Vale implies Bruce is as emotionally unavailable as ever. (Hamm has stated his Batman is about a man who allows his obsessions to screw up his sex life.)

This draft allows Bruce to grow as a person -- to reject revenge in favor of justice and to embrace his new family. It's far more sentimental than anything seen in the '89 film, and reads closer to what Joel Schumacher was attempting with Batman Forever (before everything descended into camp with the next movie).

If for nothing else, this draft is notable for predating any Frank Miller influence on Batman. The dominant view of the character in 1985 was still a reflection of the 1966 television series. This feels as if Burton and Hickson are doing a more serious adaptation of the show, maintaining much of the absurdity but reaching for genuine human drama and acknowledging the reality of 1980s urban America. Honestly, it sounds like it could've been pretty entertaining — maybe even deserving of its own comics adaptation.

0 Comments